The Importance of Four Words in the Corner

Whether you believe Jimmy molested Claudia says more about you than about Magnolia. The movie leaves little doubt where it stands, and its writer/director has been even clearer.

But it’s also correct that the full truth is and will ever remain unavailable to the audience, and to Rose.

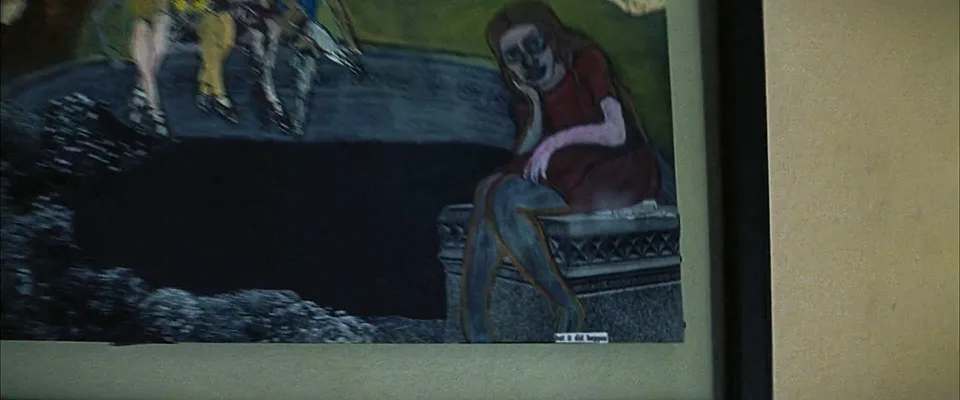

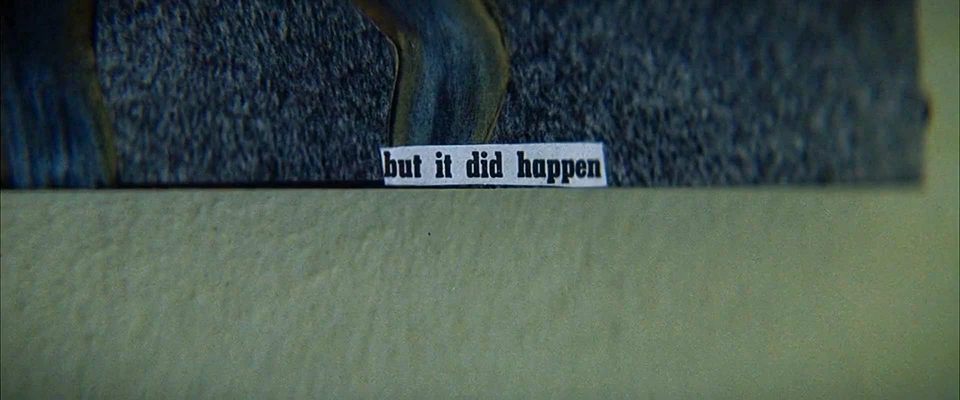

In that context, let’s look closely at the “but it did happen” text in the painting in Claudia’s apartment. It’s shown through camera movement and a zoom, and the aggressiveness of Anderson’s presentation makes obvious its purpose as a strong statement. As Matthew Sewell wrote in the Bright Lights Film Journal: “This arresting device puts special weight behind the painting’s claim that Jimmy molested Claudia.”

But for whom, exactly, is it designed? And what does it actually accomplish?

Sewell continues: “[T]hough Magnolia’s story never quite answers this question … I do not think we are meant to doubt Claudia. The cinematography here adjudicates the issue for the audience via pure authorial proclamation: It did happen. At the same time, delivering this information non-diegetically underscores that the question is not settled for the characters.”

The camera moves away from Claudia and Rose to show us the painting, and then pushes in to show us the text in the lower right corner. It’s natural to conclude that this is the author (Anderson) speaking to us (the audience).

But this is wrong in a couple of essential, related ways. First: This camera move is not only “authorial proclamation”; it quite clearly (if subtly) represents Rose seeking and finding the painting. Second: As a result, the main function of this passage is to show that the question has been settled for one character: Rose. This is a mother recognizing how she has failed her daughter.

Before getting to Rose, though, let’s dispense with the idea that this bit serves any purpose if directed at the audience.

Bluntly, “but it did happen” doesn’t do a damn thing. Without those four words, nobody is going to give Claudia’s accusation any less credence — because Anderson has already done the work to support it.

Retaining the phrase in the corner merely reinforces that Claudia’s claim is longstanding, information that we’ve already been given by Jimmy.

And it hardly seems worth mentioning that if one is inclined to give Jimmy the benefit of a doubt, this little flourish isn’t going to change that.

As a result, the only thing it seems to establish, in a cinematic address to the viewer, is its importance to Claudia, essential enough to her identity that it needed to be displayed in her apartment. More specifically, it’s a reassurance to herself that she’s not crazy, and that she didn’t make it up.

But Anderson has included a small detail — clearly intentional, and clear as day if you know to look for it — that gives those words a different and greater importance. Just before the camera begins to move away from the women, Rose looks toward the painting, and the camera follows her lead.

Her position against the door doesn’t allow her to “see” it, and it’s just a glance. So one can’t argue that she’s now discovering this text that illuminates Claudia’s relationship with Jimmy.

But it’s easy to infer what’s happening in Rose’s mind, probably subconsciously. This is a painting she’s seen dozens of times. Perhaps she’s spent some time studying it, and puzzling over the strangeness of the four words in the corner. It’s gnawed at the back of her mind, like her questions about Jimmy that she’d previously lacked the courage to ask.

And in this moment, she notices it again, and she understands. Not that Jimmy molested Claudia, because she already knew that … somewhere. Instead, Rose recognizes that Claudia has been trying tell her, in a fashion, for a long time. Her daughter put it up on the wall, an invitation to start a conversation.